Alchemy in Orbit: Can We Really Turn Water into Rocket Fuel?

I have always contended that the single biggest shackle on humanity’s ankles isn’t gravity—it’s the tyranny of the rocket equation.

The math is brutal: to go anywhere interesting in space, you need fuel. But to carry that fuel, you need more fuel to lift the weight of the fuel. It is a vicious cycle that has kept us tethered to Earth’s immediate neighborhood for decades. We are essentially trying to drive across the country with only the gas in our tank, because there are no gas stations on the highway.

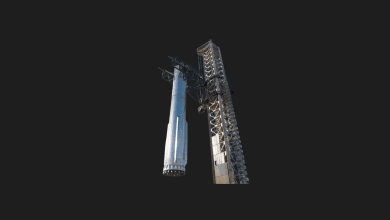

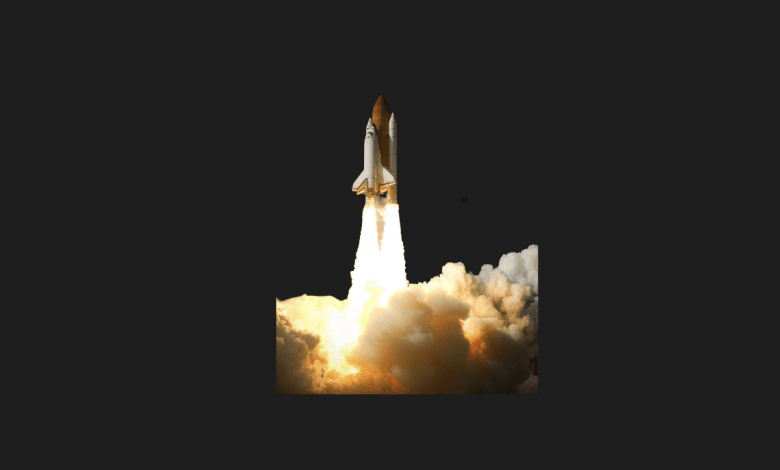

But this week, a development caught my eye that feels like it could be the first brick in building that cosmic highway. General Galactic, a startup founded by former SpaceX engineer Halen Mattison, is preparing to test a technology that sounds almost like magic: turning simple water into rocket fuel, right there in the vacuum of space.

If this works, we aren’t just talking about a new engine; we are talking about unlocking the Solar System. Let’s dive into what Mattison is planning and why this October launch on a Falcon 9 is one of the most critical tests of the year.

The “Gas Station” Problem

Here is the context we need to understand why this matters. Right now, every satellite, every probe, and every astronaut is limited by what they launch with. Once the tank is dry, the mission is over.

General Galactic is betting on water as the solution. Why water? Because it is stable, dense, and safe to launch. You don’t need complex cryogenic freezers to store it like you do with liquid hydrogen. But the real trick isn’t storing it; it’s what you do with it once you are up there.

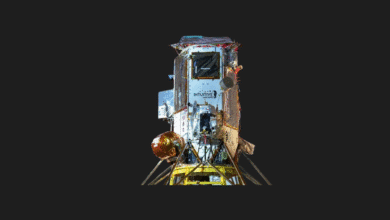

According to the latest reports I’ve reviewed, Mattison’s team is building a system called Genesis. Their upcoming mission involves a 1,100-pound satellite that will attempt to prove two very different propulsion methods using the same tank of water.

The Two-Pronged Approach

What fascinates me about General Galactic’s design is that they aren’t choosing between raw power and efficiency. They are trying to do both.

1. The Chemical Kick (The Muscle)

The first mode relies on electrolysis. If you remember your high school chemistry, you know that if you run an electric current through water ($H_2O$), you split it into Hydrogen and Oxygen.

- The Process: They split the water in orbit.

- The Result: They burn the hydrogen and oxygen together.

- The Effect: This creates a high-pressure, high-temperature reaction—a classic rocket burn. This is what you need for fast maneuvers or changing orbits quickly.

2. The Electric Glide (The Marathon Runner)

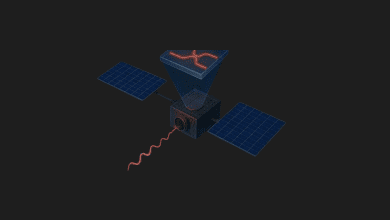

The second mode is where things get sci-fi. Instead of burning the gas, they take the oxygen produced from electrolysis and ionize it.

- The Process: They apply a powerful electric current to turn the oxygen into plasma.

- The Result: Using magnetic fields, they shoot this plasma out the back.

- The Effect: This is “electric propulsion” (similar to ion thrusters). It provides a very low thrust, but it can run for a long time. It’s perfect for maintaining orbit or slowly drifting to a new location without wasting tons of propellant.

Here is a quick breakdown of why this hybrid approach is so clever:

| Feature | Chemical Mode | Electric (Plasma) Mode |

| Fuel Source | Water (Split into H2 + O2) | Water (Oxygen Plasma) |

| Thrust Power | High (Explosive) | Low (Continuous) |

| Best Use | Rapid course correction, avoidance | Station keeping, deep space drift |

| Efficiency | Lower | Extremely High |

The Engineering Nightmare: Is It Worth the Weight?

Now, I have to put on my skeptic’s hat for a moment. While the concept is brilliant, the physics are unforgiving.

The biggest question mark hanging over General Galactic is mass efficiency.

Think about it: to split water, you need an electrolyzer. To ionize oxygen, you need heavy power supplies and magnets. To power all of that, you need massive solar panels or batteries.

The Critique: Does the weight of all this extra machinery cancel out the benefits of using water?

If your “fuel refinery” is so heavy that you could have just brought more traditional fuel instead, the math doesn’t work. This is the tightrope Mattison is walking. The system has to be light enough to make the conversion process worth the effort.

The “Acid” Test

There is another hidden danger here that I found particularly interesting. Ryan Conversano, a former NASA technologist and current advisor to the company, flagged a massive risk: Corrosion.

Atomic oxygen and ionized plasma are incredibly reactive. They love to “eat” other materials.

- If you are generating oxygen plasma inside your engine, that plasma wants to react with the walls of the thruster, the electronics, and the seals.

- It’s essentially like trying to hold acid in a metal bucket.

Designing materials that can withstand this environment for years in space is a materials science challenge that has baffled engineers for decades. If General Galactic has solved this, that alone is a breakthrough worth billions.

Why This Test Changes Everything

So, why am I so excited about a test that might fail?

Because of where water is found. We know there is water ice on the Moon. We know there is water on Mars. We know there is water in asteroids.

If General Galactic proves that we can take raw water and reliably turn it into both high-thrust chemical fuel and high-efficiency electric propellant, we stop needing to launch fuel from Earth.

- Step 1: Land on the Moon.

- Step 2: Mine ice.

- Step 3: Convert it to fuel using this tech.

- Step 4: Refuel ships in orbit.

This is the definition of In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). It is the difference between a camping trip where you bring all your own water, and building a house next to a river.

Final Thoughts

The upcoming October launch aboard the Falcon 9 isn’t just a tech demo; it’s a feasibility study for the future economy of space. If Mattison’s 1,100-pound satellite can maneuver effectively without turning into a corroded husk, we might be looking at the engine that takes us to Mars—not because it’s the fastest, but because it runs on the most abundant resource we have.

I’ll be watching the telemetry from this launch like a hawk.

What do you think? Is water the ultimate space fuel, or are we better off focusing on nuclear thermal propulsion for the long haul?