The Titanium Revolution: How Airbus is Rewriting the Rules of Aviation

I’ve been following the intersection of 3D printing and heavy industry for a while now, but what Airbus is doing right now feels like a genuine “lightbulb moment” for the future of flight. For years, we’ve talked about 3D printing as a way to make cool prototypes or small, niche engine parts. But Airbus just took the gloves off.

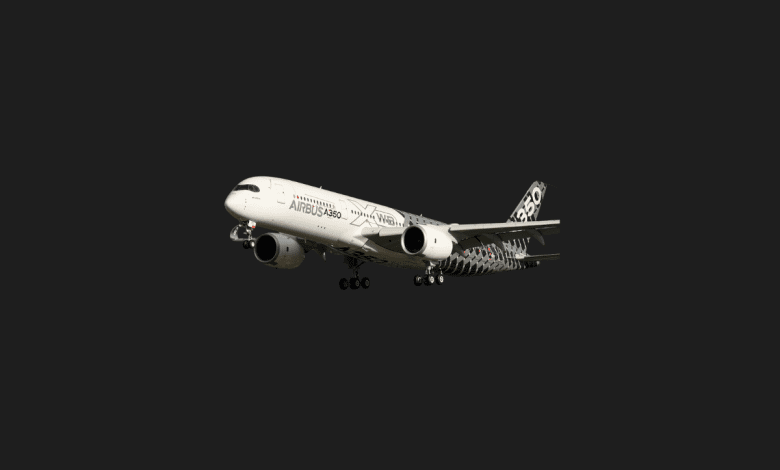

They are officially integrating w-DED (Wire-Directed Energy Deposition) technology to manufacture massive, structural titanium components. We aren’t talking about brackets the size of your hand anymore; we’re talking about components for the A350 that are essential to the plane’s integrity.

Why the “Old Way” Was Holding Us Back

To understand why I’m so hyped about this, you have to look at how we used to make plane parts. Traditionally, you’d take a massive block of titanium and carve it down (machining) or hammer it into shape (forging).

Here’s the kicker: in the aviation world, we use a term called the “buy-to-fly” ratio. With traditional methods, up to 95% of the expensive titanium you buy ends up as scrap metal on the floor before the part ever touches a runway. As someone who hates waste, that statistic always felt like a gut punch.

Enter w-DED: The Giant Robot Weaver

So, how is Airbus fixing this? Instead of starting with a block and taking away material, they are using a multi-axis robot arm that acts like a high-tech weaver.

- The Material: It uses titanium wire instead of the usual metal powder.

- The Process: A laser or plasma beam melts the wire instantly as the robot moves, building the part layer-by-layer.

- The Result: What they call “near net shape.” The part comes out of the printer looking almost exactly like the finished product.

I find the scale here mind-blowing. Most 3D printers hit a wall at about 60 centimeters. With w-DED, Airbus can print parts up to seven meters long. Plus, it’s fast. While powder-based systems measure progress in grams, this thing pumps out kilograms per hour.

My Take: It’s Not Just About Saving Money

While the bean counters at Airbus are happy about reducing costs and lead times (forging dies can take two years to make, while a 3D model is ready in weeks), I think the real win is design freedom.

When I look at these parts, I see a future where engineers aren’t limited by what a giant hammer can do. We can now design parts that are lighter, more organic, and optimized for strength rather than “manufacturability.” It’s a shift toward generative design—where the computer suggests the most efficient shape, and the printer just builds it.

Ugu’s Note: Imagine a wing structure that mimics the hollow, lightweight bones of a bird. That’s where this tech is taking us.

From Prototyping to the A350

This isn’t a “maybe” technology. Airbus has already started installing these 3D-printed titanium parts around the cargo door of the A350. They’ve passed the ultrasonic tests, they meet every safety standard, and they are flying right now.

The long-term goal? Moving this tech into the “holy trinity” of aircraft parts: wings, landing gear, and engine mounts. If they pull that off, the way we build aircraft will have changed forever.

What do you think?

If you knew a plane’s critical structural parts were “printed” by a robot rather than forged by hand, would you feel more confident in the tech, or do you still trust the old-school heavy machinery more? I’d love to hear your thoughts on this shift!