Quantum Entanglement Achieved at the Nanometer Scale

Researchers have achieved quantum entanglement between phosphorus atoms on a silicon chip at a distance of 20 nanometers. This brings us closer to reliable and scalable quantum computers.

Quantum entanglement was once a phenomenon that Albert Einstein described as “spooky action at a distance,” fascinating the scientific world for many years. Today, this phenomenon, which forms the basis of quantum computers, is defined as a special connection that forms between particles.

Although quantum computers are still in their infancy, they can perform operations that classical computers cannot, thanks to entanglement. Simulating natural quantum systems like molecules, drugs, or catalysts is just one of the possibilities this technology offers.

Now, in a recently published study, scientists have announced that they have achieved quantum entanglement between two atomic nuclei separated by a distance of approximately 20 nanometers.

This may not seem like a “huge” thing, but the method used represents a practical and conceptual breakthrough, utilizing one of the most sensitive and reliable systems for storing quantum information.

The Balance Between Control and Noise

For decades, research into quantum computers has been stuck on the incredible challenge of balancing two opposing needs. Quantum computers are so sensitive that they can be affected even by external electrons. Therefore, it is necessary to protect them from external interference and “noise.” But at the same time, it is also necessary to interact with them to perform meaningful calculations.

For this reason, many different types of hardware are still in the race to build a quantum computer. Some are successful at fast processing but are sensitive to noise, while others are well-protected from noise but are difficult to operate and scale.

Making Atomic Nuclei Talk

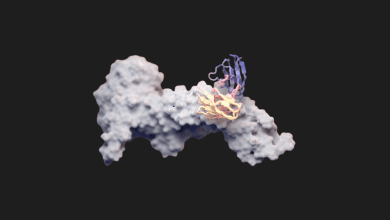

The research team had been working on a system that is primarily protected against noise. In this study, phosphorus atoms were placed inside silicon chips, and quantum information was encoded using the “spin” property of the atomic nuclei.

However, for a useful quantum computer, it is necessary to work with many atomic nuclei simultaneously. Until now, the only way to work with more than one atomic nucleus was to place them very close together in a solid material where they could be surrounded by a single electron.

Although the electron is much smaller than the atomic nucleus, quantum physics gives it the ability to “spread out” in space. This allows it to interact with multiple nuclei at the same time. Still, the interaction range of an electron is limited, and connecting multiple nuclei to the same electron made individual control of each nucleus difficult.

In the new study, the researchers explain the communication between the nuclei with an analogy: instead of people talking in the same room, it’s like they are “talking on the phone between rooms.” Each room is still quiet, but now the people (atomic nuclei) can talk to each other from greater distances. These “phones” are the electrons. Thanks to the interaction between the electrons, each nucleus can establish entanglement with other nuclei using its own electron channel.

The method used in the research is the “geometric gate” method, previously applied for high-fidelity quantum operations. This is the first time this method has enabled the entanglement of multiple nuclei in silicon via the same electron.

In the experiment, the phosphorus nuclei were separated by 20 nanometers. This distance corresponds to the scale at which modern silicon transistors are manufactured. This makes it possible to integrate long-lasting and well-protected nuclear spin qubits into existing silicon chip architecture. It is noted that in the future, this entanglement distance could be further increased by physically moving the electrons or shaping them into longer forms. The research demonstrates that advances in electron-based quantum devices can be applied to nuclear spin-based quantum computers capable of performing reliable calculations.